Danish Ancestry

Useful facts about Danish Ancestry

My Danish Roots has worked hands-on with Danish ancestry for more than 40 years. Being based in Denmark and with Danish as our first language, we are working on location, and we understand which sources to use to find the needed information. Get in touch for a free consultation, and let’s discuss how we can help you now!

Accessions

The List of Accession is a section of the parish register. In principle, the list should include information on all persons who have moved to the parish; but there is some difference in how the priests registered the information. Thus, in many cases, only servants are on the list, while farmers and other self-employed people are not listed. Similarly, in some parishes, only the head of the household is registered, while the wife and/or children are missing. In other parishes, all people were listed.

It also differs from parish to parish when the lists began. This usually happened between 1814 and 1830. In contrast, all lists in the cities ceased in 1854 and in the parishes in 1873.

The accession list contains the following information for each person:

- Name

- Date of arrival to the parish

- Age

- Occupation, employment

- The parish from which the person came

- A reference to the Comparison Directory in the parish register

- Remarks, possibly the place of birth

Adoptions

Until the middle of the 19th century, adoption was rare. It was typically foster children. Eventually, a more formal affiliation was introduced but mostly foster children were adopted; for instance, family members who had taken care of an illegitimate child. But there were also anonymous adoptions, where the child was handed over to unknown adoptive parents.

In any case, it was entered in the parish register that the child was adopted.

Adscription (a form of Serfdom)

Adscription, The “Stavnsbånd” was a serfdom-like institution introduced in Denmark in 1733 in accordance with the wishes of estate owners and the military. It bonded men between the ages of 14 and 36 to live on the estate where they were born.

The institution was introduced to alleviate a serious agricultural crisis in the 1730s. Demand from Denmark’s traditional export countries was falling, and people were migrating to the cities, which meant that it was difficult to man the estates. Furthermore, the military needed men for the militia. Military service at the time was in practice delegated to men who were less able in agriculture because it was the estate owner’s duty to delegate men to the militia. The age limit was changed three times; in 1735 to 14–36 years, in 1742 to 9–40 years, and in 1764 to 4–40 years.

The “Stavnsbånd” was gradually abolished as part of agricultural reforms starting in 1788. At first, the reform affected only those under the age of 14. Thereafter, it affected those who were over the age of 36, and then those who had served in the military. By 1848, the introduction of military conscription meant the final transformation of the “Stavnsbånd”, since men could now legally reside in any district they wanted.

Censuses 1765-1970

Censuses in the Kingdom of Denmark:

- 1765 (Ringkøing, Ribe, Tønder Skanderborg Vejle, Haderslev, Åbenrå, Sønderborg, Odense, Svendborg, Frederiksborg)

- 1771 “Oeder’s “(Copenhagen, Holbæk, Sorø, Frederiksborg, Roskilde, Præstø)

- 1787

- 1801

- 1834

- 1840

- 1845

- 1850

- 1855

- 1860

- 1870

- 1880

- 1885 (Copenhagen)

- 1890

- 1895 (Copenhagen)

- 1901

- 1906

- 1911

- 1916

- 1921

- 1925

- 1930

- 1940

- 1950 (not yet published)

- 1955 (lost)

- 1960 (not yet published)

- 1970 (not yet published)

Censuses in Schleswig:

- 1769

- 1801/1803

- 1834/1835

Censuses in Holstein and Dithmarchen:

- 1769

- 1803

- 1835

Censuses in Dansk Vestindien/US Virgin Islands:

- 1841

- 1846

- 1855/1857

The information in the censuses differs very much from one census to the next. Generally, the newer census the more facts. One should keep in mind that information of the censuses may be inaccurate.

Census by Copenhagen Police 1890-1923

Copenhagen Police kept census records of all citizens 14 years or older during the period 1890-1923. Children were registered together with their father.

The records contained information about

- Occupation

- Family members

- Addresses

- Important notes

The Central Person Register (CPR)

It is a national register with basic personal information about anyone who has a social security number.

All people with residence in Denmark since April 1, 1968 (Greenland May 1, 1972) are in the register which is updated continuously.

Christening

Throughout the ages, there have been different practices in Denmark for when the christening should take place:

- In 1539 it was decided that christening should take place on the first or second Sunday after birth

- In 1643, under Christian IV, it was decided that christening should take place no later than eight days after birth

- In 1771, the requirement for quick christening waived, taking into account the life and health of the child in the unheated churches

- In 1828 it was decided that the child should be christened no later than eight weeks after birth, and the christening should take place in the church (as opposed to home baptism)

Children who were privately christened because of weak health were to have their christening confirmed in the church as soon as possible. In 1828 the laws were changed so that the child had to be christened no later than eight weeks after its birth, which made it easier for the mother to attend the child’s christening, see “Churching of women” on this page.

Until the 1849 Constitution, everyone was obliged to have their children baptized (with the exception of Jews)

Until 1854, a child was only entitled to inherit once he had been baptized.

Children who were privately christened because of weak health were to have their christening confirmed at the church as soon as possible. The confirmation was not a christening because one can only be christened once.

Today, most people choose to hold a christening when the child is around 3 months old. In reality, the christening can be whenever it suits the parents, as long as the child is named before it is 6 months old.

Christening - Illegitimate children

Originally, the term ”illegitimate children” wasn’t used, but rather two different terms:

- “Slegfredbørn” (“bastards” according to the dictionary)

- “Horebørn” (No term given in the dictionary, literally translates to “whore children”)

Slegfredbørn were children of parents who lived together but weren’t married, and horebørn were children where one or both the parents were married to someone else. They didn’t have the same legal status; horebørn were less favored.

Legitimate child or not?

The term “illegitimate children” is introduced with the Christening Decree of May 30th, 1828. The legitimacy of the child was determined by the marital status of the parents at the time of the christening. If they married the same day (but before) the child was christened, it would be a legitimate child.

1683

According to Danske Lov [Danish Law] of 1683, it was a punishable offense to have intercourse outside of marriage. The man could be sentenced to marry the woman or to provide annual alimony to her to help provide for the child.

1767

Until 1767, the mother of an illegitimate child had to make a public confession to the congregation, and the alleged father had to either acknowledge his fatherhood or swear that he wasn’t the father of the child.

After 1767, the punishment for both parents was 8 days imprisonment; and until 1812, they were also fined. Soldiers and sailors in the navy were exempt from the fines the first time they had a child out of wedlock, however.

1866

From 1866 and all the way up to 1933, the offended party in a marriage could demand that the spouse be punished with jail or fines.

Illegitimate children’s Family Names

In the case of a child being born out of wedlock, the alleged father would have to give his consent for the child to carry his family name or patronymic. Otherwise, the mother was to name the child after herself, her father, or after the place of birth. These rules, however, were not strictly abided by all of the time.

Christening - Sponsors

Children who are christened in the Danish National Evangelical Lutheran Church must have 2-5 sponsors who can testify that the child has been christened.

The sponsors can be family members or friends, but in any case it should be people who share the parents’ values and have their great trust.

A sponsor must be at least 14 years old, i.e. the normal confirmation age.

According to “Danske Lov” [Danish Law, a nationwide law from 1683], those who were to bear witness or be sponsors at a christening, had to be honest people

The person who carries the child to the christening and responds “Yes” to being christened on behalf of the child is called the godmother/godfather but this is not clerical term.

An unchristened mother can’t carry her child herself, as both the person carrying the child and the sponsors must be christened with the Christian faith, but membership of the Danish National Evangelical Lutheran Church is not a prerequisite. For example, a Catholic christened can both carry and be a sponsor at a christening in Danish National Evangelical Lutheran Church.

To this day the sponsors still have the same duty.

Churching of Women

The ”churching of women” ritual is a custom that has ties to the Old Testament, specifically the Leviticus. According to it, a woman that has given birth to a son is unclean for seven days and then has to stay at home for another 33 days, making a total of 40 days. If she gives birth to a daughter, the number of days is doubled; a total of 80 days. However, the then Catholic Denmark did not follow the rule of 80 days, but only the 40.

When the 40 days were up, the woman in confinement would go to the church, kneeling before the priest outside of it. The priest would sprinkle her with holy water and say prayers. Afterward, the woman would be handed a wax candle as a sign of her reentering the Kingdom of God. The candle would be lit if the child was alive, and unlit if it was dead. The mother would often get a candle with her in the casket if she had died in childbirth.

The woman was now considered cleansed, and the priest would lead her inside the church, where she would make a sacrifice, often consisting of wax candles and money.

Later on, when Denmark became Protestant, the churching was reinterpreted as a Lutheran thanksgiving and admonition ritual, reminding the woman of her responsibility as a mother.

At the beginning of the 1900s, the ritual faded out, though there are some instances where it was used even decades after that period.

Confirmation

To be confirmed, a child should be at least 14 years old. If not, the bishop had to issue a dispensation.

Until the middle of the 19th century, the confirmation was an extremely serious affair. Not only should the children confirm their Christian baptism. They also had to pass a rigorous exam, which included both a test in Christianity and an assessment of whether they were mature, sensible, and well-dressed enough to step into the ranks of adults and obtain some fundamental civil rights.

If one wasn’t confirmed or didn’t pass the knowledge test, one couldn’t for instance:

- Terminate schooling

- Marry in a church

- Seek work outside own parish

Thus, it was to be understood quite literally that the Confirmand entered the ranks of the adults.

The right to take a child out of school continued to be associated with the confirmation right up to the 1960s. Some children from low-income families stopped as soon as they were confirmed because their working power was needed.

After the June Constitution of 1849, the link between confirmation and civil rights became looser, but it was not until 1909 with the “Royal Order on Confirmation” that the modern confirmation was born. Now school and church were separated, so the confirmation alone was an ecclesiastical act and a ritual in the local community.

An important provision was that the priest observes that the exam should not be a test of knowledge, but a conversation for the edification of youth and the congregation present.

Another paragraph stated that the priest and church attendant could not require payment for the preparation or the confirmation.

The last thing was to tone down the confirmation as proof of the family’s financial capacity. But even though the payment to the priest lapsed, it did not change the fact that the confirmation continued to be a ritual that marked not only the Christian faith and the transition to adulthood but also the ability of the family to afford a beautiful set of clothes and a party.

The “Royal Order on Confirmation” designated two regular annual confirmation Sundays, Sunday after Easter in the spring and Sunday after Mikkel’s day in the fall.

Confirmation - Grades

When a child was confirmed, one set of grades was given for each of Knowledge and Conduct on the scale:

- Ug = Udmærket godt (Outstanding)

- Mg = Meget godt (Very good)

- G = Godt (Good)

- Tg = Temmeligt godt (Pretty good)

- Mdl = Mådeligt (Mediocre)

- Slet = Slet (Bad)

The scale was also used at schools and was in use from 1805 through to 1963.

Copenhagen Registry offices 1848-1939

The registry offices were private companies that mediated contact between job-seeking servants and households. In this way, the offices acted as a private employment agency.

The protocols from the 12 different Copenhagen registry offices are rich in personal information and tell about working life and working conditions from 1848-1939. In addition, they can also provide insight into working life for a large group of Copenhageners. The individual registry offices kept two sets of protocols, namely servant and husband protocols, where inquiries from servants and husbands, respectively, are entered chronologically.

The history of the offices in Copenhagen dates to 1728, when a royal decree ordered the Corporation of Copenhagen to appoint two men to help maids find homes to serve in. With the Civil Service Act of 1854, the profession was regulated. It was decided that the registry offices should keep lists of both servants and husbands in approved protocols authorized by the Corporation of Copenhagen. In addition, tariffs were set for how the offices could be paid.

In 1901, the attachment offices faced competition from the municipal employment service but continued to exist until the 1930s. During their lifetime, the registry offices were repeatedly criticized for having a mildly tarnished reputation.

Counties - 49 in the years 1662-1793

- Åstrup, Sejlstrup, Børglum

- Dueholm, Ørum, Vestervig

- Aalborghus

- Skivehus

- Mariager Kloster

- Hald

- Dronningborg

- Bøvling

- Lundenæs

- Silkeborg

- Kalø

- Skanderborg

- Havreballegård

- Åkær

- Riberhus

- Koldinghus

- Stjernholm

- Hindsgavl

- Assens

- Rugård

- Odensegård

- Nyborg

- Tranekær

- Halsted Kloster

- Ålholm

- Nykøbing

- Møn

- Vordingborg

- Tryggevælde

- Roskilde

- Ringsted

- Korsør

- Antvorskov

- Sorø

- Sæbygård

- Kalundborg

- Holbæk

- Dragsholm

- Jægerspris

- Kronborg

- Frederiksborg

- Hørsholm

- København

- Bornholm

- Haderslev Øster (established in 1789)

- Haderslev Vester (established in 1789)

- Åbenrå og Løgum Kloster

- Tønder

- Sønderborg og Nordborg

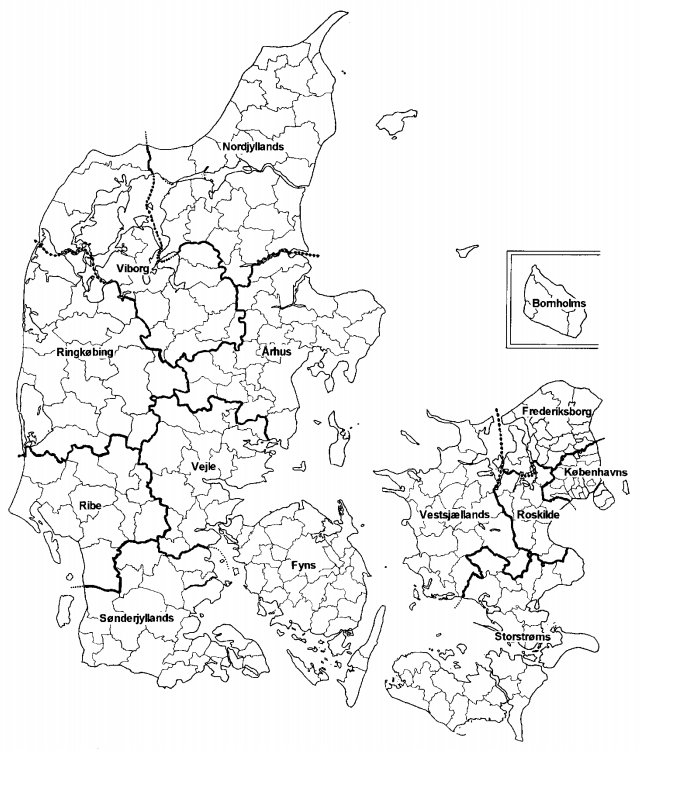

Counties - 24 in the years 1793-1970

- Hjørring

- Thisted

- Ålborg

- Viborg

- Randers

- Ringkøbing

- Ribe

- Århus

- Skanderborg (1824-1867, 1942-1970)

- Vejle

- Tønder (1920-1970)

- Haderslev (1920-1970)

- Åbenrå 1920-1970)

- Sønderborg (1920-1970)

- Odense

- Svendborg

- Holbæk

- Frederiksborg

- København

- Roskilde (1793-1808)

- Sorø

- Præstø (1803-1970)

- Maribo

- Bornholm

Counties - 14 in the years 1970-2006

- Københavns municipality

- Frederiksberg municipality

- København

- Frederiksborg

- Roskilde

- Vestsjælland

- Storstrøm

- Fyn

- Sønderjylland

- Ribe

- Vejle

- Ringkjøbing

- Viborg

- Nordjylland

- Århus

- Bornholm

Counties/Regions - 5 since 1970

- Nordjylland

- Midtjylland

- Syddanmark

- The capital

- Sjælland

Danish National Church "Folkekirken"

The Danish National Evangelical Lutheran Church (Folkekirken) has typically one church in each parish. A few parishes have more than one church, though.

Earlier there was one and only one incumbent in each parish. Today a parish can have more incumbents of which one will be appointed to be responsible for the church book. And an incumbent can serve more than one parish.

Danish letters

The Danish alphabet has three additional letters:

- Æ – æ

- Ø – ø

- Å – å

æ = ae

Has its roots in Latin, and has been part of the Danish language for about a thousand years.

ø = oe

As ‘æ’ it has its roots in Latin and has been part of the Danish language for about a thousand years.

å =aa

Until 1948, the letter was officially written as “aa”, but now “å” is the official spelling, although many names of cities or families still are spelled with “aa”, e.g. the city of Aalborg. Most Danes perceive “aa” to be a little more sophisticated than “å” in names.

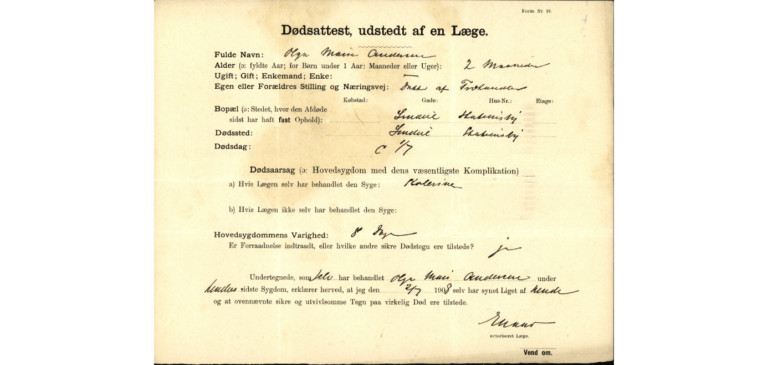

Death certificate

The death certificate has the following information about the deceased:

- Her full name, Olga Marie Andersen

- She was 2 months old when she died

- Daughter to a timber merchant [no name of the father]

- The cause of death was acute enteritis

- She died 1 July 1908 after having been ill for 8 days

- The doctor who treated her made an inspection of her body the next day

Emigration

Between 1868 and 1914 around one out of ten, or 287,000 Danes emigrated. Most of the people entered into a contract with an agent who made all the arrangements but not all did. The police wanted to watch the agents and their businesses and as of May 1, 1868, the agents were ordered to share copies of their contracts with emigrants. These registrations are available for genealogists today. Other sources are passenger lists of the shipping companies, lists of expunctions of the church books, and the authorities at the arriving destinations like Ellis Island.

Many different routes

Basically, emigrants traveled directly from Denmark to the destination non-stop or indirectly from Copenhagen to another European harbor, e.g. Hamburg, Liverpool, Rotterdam, Bremen (Bremerhaven), Christania (Oslo).

The journey

During the second half of the 1800’s emigrants eventually traveled by trains from their native soil to the departure harbor and they crossed the Atlantic Sea by steamboat. This reduced the traveling time from around 3 months to 2-3 weeks from their home in Denmark and to their new home in America.

On top of that, the costs of the ticket decreased and were around 125 Danish kroner – compared to a skilled worker’s average yearly income of around 600 kroner.

De facto expulsions

The Copenhagen Police urged quite a few criminals, dropouts, and potential troublemakers to emigrate to America, Canada, or South America.

In total, 1,101 unwanted people were supported ‘morally’ and economically by the Copenhagen Police. This approach was illegal and was rapped by the receiving countries.

Emigration Ships to America

- Harald

- Thingvalla

- Geisir

- Island

- Hekla 1

- Heimdal

- Hekla 2

- Danmark

- Norge

- Amerika

- Oscar II

- Hellig Olav

- United States

- C.F. Tietgen

- Frederik VIII

1880-1881

1880-1900

1882-1888

1882-1904

1882-1883

1883-1884

1884-1905

1889-1889

1889-1904

1893-1897

1901-1930

1902-1931

1903-1925

1906-1913

1913-1935

Expunctions

The List of Expunction is a section of the church book. In principle, the list should include information on all persons who have moved out of the parish; but there is some difference in how the priests registered the information. Thus, in many cases, only servants are on the list, while farmers and other self-employed people are not listed. Similarly, in some parishes, only the head of the household is registered, while the wife and/or children are missing. In other parishes, all people were listed.

It also differs from parish to parish when the lists began. This usually happened between 1814 and 1830. In contrast, all lists in the cities ceased in 1854 and in the parishes in 1873.

The list contains the following information for each person:

- Name

- Date of leaving the parish

- Age

- Occupation, employment

- The parish to which the person moved to

- A reference to the Comparison Directory in the church book

- Remarks, possibly the place of birth

Headstones

There are seven conservation criteria for headstones and memorial stones in Danish cemeteries:

- All grave monuments that are more than 100 years old should generally be considered worthy of preservation

- Of the grave monuments that have been typical of the cemetery over time, at least one copy of each type should be preserved for posterity

- Grave monuments whose decoration is of particular interest

- Grave monuments with local historical names

- Grave monuments with particularly rich and interesting inscriptions

- Tombstones made by recognized artists or who have special art historical interest

- Memorials that preserve the memory of deserving men and women

Grave sites

Grave peace is the peace that must be granted and observed around the body or ashes of a dead person. It is ensured, among other things, during the conservation period, which is the period when a burial site cannot be demolished. In Denmark, the preservation period is at least 20 years for a coffin burial site and at least 10 years for an urn burial site, for the most recently buried coffin or urn.

The purpose of the conservation period is for the burial site to remain untouched for such a long time that the coffin, urn and remains have decomposed and perished in the ground. Although the law states that the conservation period is at least 20 and 10 years, it is not uncommon for the conservation period to be 25 and 30 years or longer. It always depends on the individual cemetery’s soil conditions, which can lead to a longer decomposition process.

When the conservation period has expired and the family no longer wishes to preserve the burial site, it can be demolished, which means that the gravestone, plants, structures etc. are removed. The tombstone is the property of the family, and it must therefore decide what should happen to the tombstone.

When a gravesite is closed, it reverts to the cemetery. This means that the burial site can be used for burial or other purposes. The burial site cannot be used for new burials until the conservation period has expired.

When new graves are to be dug at old burial sites, old bones often turn up. They are placed back in the grave and the digger covers them with earth before the grave is put into use again.

The Danish cemeteries are burial grounds for everyone, regardless of whether you are a member of the national church or not.

Levy rools

A levy roll is an index of people bound for conscription, going back to 1789.

1789

From 1789-1848, all boys of the peasant class were entered into the levy rolls from birth.

1849

In 1849 a law on general conscription were instated, meaning that all males were now entered into the rolls, but only after they had been confirmed [usually at age 13-15].

1860

Between 1860-1869, boys were entered into the rolls at the age of 16.

1869

From 1869 they were entered at age 18.

The entries are registered per recruiting area which since 1788 usually is the same as the parishes.

The levy rolls have information about:

- The number of the recruiting area

- The boy’s old and new number

- The names of the boy and his parents

- The boy’s parish of birth

- His year of birth

- His height (Danish inches)

- His whereabouts

- Notes with information about his military services

When a man is no longer fit for military service (for instance due to his age), his name is crossed out.

The levy rolls ate often very difficult to interpret due to the many abbreviations.

Names - Boys

The 10 most common names for boys and men in 1801/1803 were :

- Peder (Peter, Petter)

- Hans (Hanss)

- Jens (Jenss)

- Niels (Nils, Njels, Nels)

- Christen (Kristen, Kresten, Cresten)

- Anders (Anners)

- Rasmus (Rassmus, Rasmuss)

- Søren (Sören, Sørren)

- Lars

- Christian (Cristian, Kristian)

In 2024, 5 of the old names still are on Top-10:

- Peter

- Michael

- Lars

- Jens

- Thomas

- Henrik

- Søren

- Christian

- Martin

- Jan

The 2024-list of new-born boys is completely different

- Noah

- William

- Alfred

- Carl

- Aksel

- Emil

- Oscar

- Malthe

- Oliver

- Arthur

Names - Girls

The 10 most common girl names in 1801/1803 were:

- Anne (Ane, Anna, Ana, An, Ann)

- Maren (Marn, Marren)

- Karen (Caren, Karn, Karren)

- Kirsten (Kiersten, Kiesten, Kisten, Kjersten, Kjesten)

- Maria (Marie, Mari)

- Mette (Methe, Mætte, Metthe, Mett, Met)

- Johanne (Johane, Johanna, Johana)

- Else (Elsa)

- Catharina (Catarina, Catarine, Catarin, Catharine, Chatarina, Katarina, Katharina)

- Ellen (Ellin, Ellien)

The ten most used names were all Christian names borrowed from biblical women or saints. The spelling of all these names could vary significantly.

In 2024, 5 of the old names still are on Top-10:

- Anne

- Mette

- Kirsten

- Hanne

- Anna

- Helle

- Maria

- Susanne

- Lene

- Marianne

The 20-24-list of new-born girls is completely different:

- Frida

- Olivia

- Alma

- Ella

- Agnes

- Emma

- Ellie

- Luna

- Sofia

- Karla

Names - Family

The 10 most common family names in 1801/1803 were:

- Jensen (Jenssen)

- Nielsen (Nilsen)

- Pedersen (Petersen, Pettersen)

- Hansen (Hanssen)

- Christensen (Kristensen, Chrestensen)

- Andersen (Anderssen)

- Larsen (Larssen)

- Sørensen (Sörensen)

- Rasmussen (Rasmusen)

- Jørgensen

In 2024, the Top-10 has the exact same names and the order is only a little different. Most importantly is that Nielsen now the most common family name:

- Nielsen

- Jensen

- Hansen

- Andersen

- Pedersen

- Christensen

- Larsen

- Sørensen

- Rasmussen

- Jørgensen

In total, there are around 147,000 different family names in Denmark of which 12,000 are patronymic family names, i.e. with the “sen” at the end.

More than half the Danish population has a patronymic family name.

Names -

The Danish name tradition

Originally, children’s family names were patronyms, i.e. -søn and later -sen (son) for boys and -datter (daughter) for girls.

1828 – Free choice of the family name

In 1828, Frederik VI issued a christening decree, in which it was stated that every child should be christened “not only with a first name, but also with the family name that it should bear in the future.” The priests were to ensure that the children were not christened “inappropriate names.” It is said that this provision was caused by a case with a man who had wanted to pay tribute to the Danish aquavit by calling his daughter Snapsiana.

The Christening Ordinance gave no answer as to who should decide what the children should be named. Therefore, it was followed up by a circular that stipulated that if the family did not already have a family name, it was up to the father to determine the child’s surname. The fathers were even given a number of choices when choosing surnames for the pods:

- The father’s own surname

- Father’s first name followed by a -sen (patronymic)

- A place name that the family was associated with

The circular also stated that all siblings should bear the same surname. For the women, this meant in practice a farewell to the custom with the father’s first name followed by -daughter.

It was not without problems to introduce laws that went against centuries-old traditions. Particularly in the rural parishes, the attitude was that the authorities, with their naming rules, stuck their noses into something that did not strike them. It was edible that all children should have the same surname, and after 1828 the female patronymics disappear just as quietly. It was worse with the fixed family names and that the children would often get the father’s surname, which was actually the grandfather’s patronymic.

In many places, they chose to interpret the circular in such a way that each generation had to decide their own family name. And thus, the whole idea of the name law was lost.

1856 – Same family name for future generations

Therefore, in 1856 it was emphasized that the family name chosen according to the 1828-law was to be the family name in the future; not just for one generation. However, the implementation of these new naming rules was still hesitant in many rural parishes and the naming practice for children born in the second half of the 19th Century differed from parish to parish.

Due to the naming changes some women would eventually change the family name from -datter to -sen. A girl christened Cathrine Pedersdatter could for instance be Cathrine Pedersen at her death.

If a person had more than one given name, it could vary which name(s) were used as well as the order of the names. The spelling of the names was quite inconsistent in the earlier days.

Nightmen

The nightmen were peculiar people who lived scattered around Jutland in the remote moor areas. They constituted entire small communities.

They had many names: nightmen, rascals, pranksters, thugs, and more, but they must not be confused with the gypsies, who were completely different people with foreign-sounding names, whereas the nightmen had “good, Danish” names. It was a disliked people that the rest of the population preferred to avoid. Many of them were not very settled but moved around the country, which can be seen from the fact that their children were born in very different places in Jutland. This meant that you were not happy to see them in the parishes when they came to beg, and if you saw that one of the women was pregnant, they were certainly eased across the parish boundary if it was not too late. There are examples of prohibitions against letting strangers spend the night in barns if you did not know them or they were not born in the parish.

The night man was the one who took care of cleaning (in the cities), chimney sweeping, and the bodies of those condemned to death, either at the gallows or outside the cities at certain places of justice. Moreover, it was the night man who in the countryside had to beat down the farmers’ old cattle and skin them, just as they did with the animals that died by themselves. The peasants could not imagine that they would have to do such dirty and dishonest work.

A nightman and his sons could not become soldiers, as they were not wanted in the service with the possible harmful consequences that might bring.

Order of Dannebrog

The silver cross of the Order of Dannebrog was instituted in 1808 by King Frederik 6. It was bestowed on “anyone who, by the wise and reasonable pursuit of the brothers’ well-being and by a noble deed, has benefited the mother country”. The cross, which is entire silver, bears the same motto and inscriptions as the Knight’s Cross and is worn in the same kind of ribbon without rosette on the left dress look.

Originally, the cross was in practice awarded as an appreciation for an effort that did not qualify to the lowest degree of the Knight’s Cross, and it was typically given to lower-ranking officials, e.g. parish bailiffs, superintendents, station managers, councilors, postmasters, lighthouse keepers, etc.

The silver cross of the Order of Dannebrog was also awarded to veterans of the Three-Year War (1848-1850) and the Second Schleswig War (1864) in a special edition in which the gaps between the crowns of the crown were not cut.

During these Schleswig wars of 1848-1850 and 1864, around 2,200 crosses were awarded to brave soldiers. Around 1,600 surviving veterans received the cross from 1924 through 1928.

The Danish Royal Court has biographies of many men of the silver cross Order of Dannebrog. The biographies are shared to direct descendants on inquiry.

Parishes

Denmark has 2,169 parishes, varying a lot in size; a little more than 100 parishes have less than 200 parishioners while a little less than 100 parishes have more than 20,000. Today, the biggest parish is Vesterbro in Copenhagen with around 45,000 people.

The parishes have also been part of the temporal administration, eventually, some of the temporal parishes differed from the ecclesiastical ones.Parishes

Denmark has 2,169 parishes, varying a lot in size; a little more than 100 parishes have less than 200 parishioners while a little less than 100 parishes have more than 20,000. Today, the biggest parish is Vesterbro in Copenhagen with around 45,000 people.

The parishes have also been part of the temporal administration, eventually, some of the temporal parishes differed from the ecclesiastical ones.

Parish registers 1611 -

The content of the parish registers has varied considerably over time. The very first parish registers are from the 16th century. In 1645, it was required by law to keep the parish registers. However, the law did not lay down any detailed rules on how records should be kept. Therefore, there is great variation in the content of the parish registers 1814. In most cases, the registers were kept in one copy only which is why many of them have been lost due to poor storage conditions, parsonage fires, etc.

The oldest preserved church book is from Nordby parish on Fanø, and the earliest entries are from 1611 and thus originated long before, it was required to keep church books in Denmark.

A lost parish register from Nakskov 1572 is known by hearsay.

By an ordinance of December 13, 1812, it was decided that the parish register should be kept in duplicate: “Hovedministerialbogen” and “Kontraministerialbogen”. At the same time, they should be grouped by event, i.e. christenings, confirmations, weddings, burials, accessions and expunctions.

Royal Maternity Hospital & Orphanage

The Royal Maternity Hospital & Orphanage (Den Kgl. Fødsels- og Plejestiftelse) was established in 1785 and was a parish by itself.

The Maternity Hospital made sure that women could give birth anonymously and in a proper environment. Both unmarried and married women could give birth in the hospital and they could keep secret the father’s name and their own if they wished.

An orphanage was also part of the hospital, where the children who were left by their mothers could live until they could be placed in a foster family or were adopted.

School Attendance

From the Middle Ages and well into the 1900s; the church was in charge of the schools, and the minister or the rural dean acted as the teachers’ superiors.

In 1814, compulsory school attendance was introduced in Denmark. School attendance lasted from age 7 until they were confirmed, typically at the age of 14.

The schooling in the towns was very different from that in the countryside: There were fewer children in the classes in the common schools of the towns than the schools in the countryside, where several age groups were gathered in each class. The village schools had typically only two classes and the children were divided according to age.

Most children attended countryside schools, though these schools were generally poorer equipped and attendance lasted fewer years than was the case with schools in the towns.

It was determined that the schools should be placed so that no child had more than a quarter-mile [almost 2 km as 1 Danish mile = about 7.5 km] to school. In sparsely populated areas, a teacher could instead go around and teach the local children 2-3 different places. In return, the teacher would enjoy shelter and catering where the teaching took place.

There was a difference in how long the children went to school. In the towns, they had to go all weekdays, while the rural children could do with three days a week. The village schools were closed for four weeks from the start of the harvest. On top of that, parents and husbands had the right to keep children (including service boys and girls) over 10 years at home from school for 2-3 weeks in the spring and 3-4 weeks in the autumn, when there was a clear need for labor in farming.

It was clear that the legislators did not believe that children in the countryside needed the same sophisticated education as the children of the towns, but they took also into account the needs of the peasants for labor.

The special form of schooling in the countryside survived in some areas until well into the 1950s.

The children were taught reading, writing, mathematics, Bible history, and the shorter catechism, and there was an examination every year. The children in the towns had subjects that were considered unnecessary for village children.

Conditions were quite harsh; corporal punishment of different kinds was common, many schools weren’t cleaned properly, and the classrooms were often overcrowded. However, one of the bright spots of going to school was going on the yearly school excursion, where the children got a break from studying and got to visit some interesting or charming places.

The school in the country

Both in the countryside and in the cities, it was common for children to earn money for the family by working. In many places the children only went to school every other day. And in the countryside, the children often only went to school in the winter. In the summer, they had to help the family look after the farm.

The school in the city

In the cities, a number of children went to private civil and real schools. It was especially the rich who could afford to send their children to fee-paying schools. Here they could get better and more education than in the public schools.

In 1899, there were new rules for the primary school. There could be no more than 37 children in the classes in a village school and 35 children in a city school.

The new subjects in the year 1900

There were new subjects such as mathematics and physics and in the city schools also mathematics and languages. The girls had to learn needlework and gymnastics so that they could prepare for their future as maids and housewives. They had to learn order and hygiene and cook healthy and cheap food.

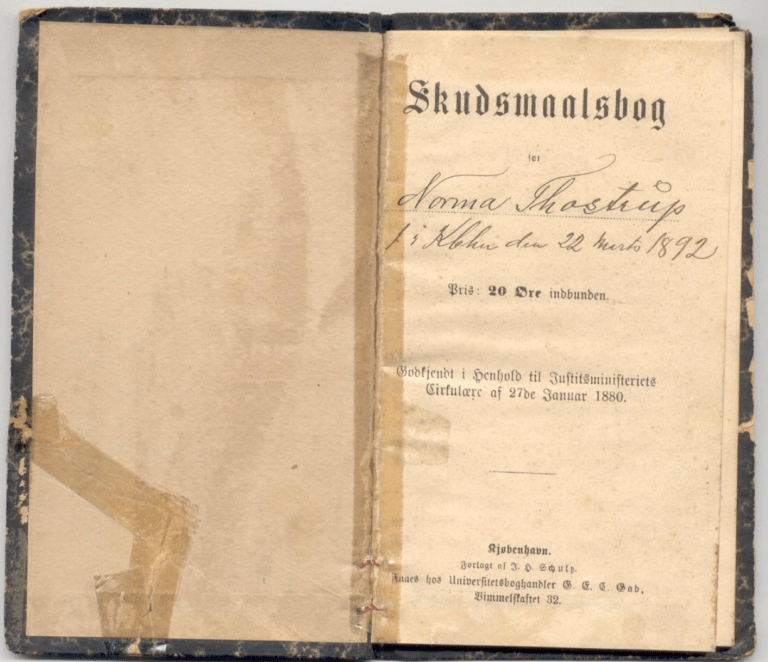

Servant’s Conduct Book

Every servant had to have a servant’s conduct book. Before use, it must be provided with a seal from either the police authority (in Copenhagen and in the market towns) or from the incumbent (in the rural areas). In 1742, the age limit was expanded further so it then included males from age 9-40, and in 1764 it was expanded even further to the age 4-40.

A child who wanted to serve after having completed school, had to obtain a servant’s conduct book if they didn’t already have one, and the book should be provided with their school certificate, when and where the child was born, if the child was christened and confirmed, and if that was the case, where and when.

Any householder who employed a servant, had to provide the servant’s conduct book with information on the when the servant worked for him, what the pay was, and what kind of work was provided. Anyone who moved to a market town or cure where they haven’t been before, to work as a servant, had to notify either the police authority or the incumbent so they could certify the servant’s conduct book.

The servant had to also notify the proper authorities when moving from the market town or cure. Not having or updating the information in the servant’s conduct book properly was punished with fines. Removing pages or purposefully making information in the book illegible is punished with either fines or prison.

Smallpox Vaccination

For centuries, smallpox (variola) had ravaged most of the world. It was a highly contagious infectious disease that resulted in high fever and blisters all over the body. Mortality was often 10-25%. If one survived, one was subsequently immune to the disease. Folklore believed that the body’s unclean fluids tried to get out using the smallpox bladders, and if they did not come out, one could become leprous. Various treatments were tried, ranging from leeches and cupping, which were to take the unclean liquid, to the risky inoculation, in which matter was inoculated from a diseased smallpox bladder into a healthy human being.

The children of Denmark have been vaccinated against smallpox since 1810. In order to be able to go to school, get married, and serve in military amongst other things, you were required to document that you had either overcome a variolous disease or get a vaccination.

In 1871 the vaccination was compulsory when a child reached 7 years. If a child was not vaccinated, the parents were fined.

For genealogists, vaccination can be a useful tool to confirm you have the right person, as both confirmation registrations and marriage registrations often show when the person in question was vaccinated and by whom.

Sources

There is a great number of Danish genealogy sources. Some of them are online but even more are available at the Danish archives. Rigsarkivet [The National Archive] in the center of Copenhagen has the greatest collection of sources available to the public. Fortunately, My Danish Roots is located near the archive.

Nonetheless, the church books and the censuses form the starting point of most genealogy research as these sources hold a lot of information about the individuals.

The content of these records changed significantly over time. A record of more recent date generally has more details than older ones.

We substantiate all our findings with similar copies of the source records. They will, of course, come in higher resolution and be readable.

We copy the full page of the source and name the files with the full information about it:

- Church book: NAME OF PERSON, Event, Date, County, Parish, Period, View#, Entry on page

- Census: Year, CENSUS, Date, Name of key person, County, Parish/Address, View#, Entry on page

Sources - Availability

- Information about individuals’ private affairs

- Parish registers

- Censuses

- Civil marriages

- Levy rolls/herdbooks

- Probate records, probate proceedings and wills

- Death certificates

- Midwifery records

- Orphanages and other social institutions

- Search tools

- National registers

- Estate archives

- Archives handed over to the National Archives

- Security of the state/defense of the kingdom

- The kingdom’s foreign policy and interests

- The Royal House

- Exam results

- Family law cases

- The archive of the Ministry of Defence

- Citizenship cases

- The Royal Family Christian 7 and older kings

- The Royal Family Frederik 6 and 7, Christian 8

- The Royal Family Christian 9 and 10, Frederik 8

- Motor vehicle registration

- Personnel matters

- Private archives

- Lawsuits – civil cases

- Court cases – criminal cases

- Registered documents, deed and mortgage

- Immigration matters

- 75 years

- 10/50/100

- 75

- 50

- 75

- 75

- 75

- 75

- 75

- 20/75

- 75

- 0

- 20

- 60

- 30

- 100

- 75

- 75

- 60

- 75

- 0

- By application

- By application

- 20

- 75

- 75/80

- 75

- 20/75

- 0

- 75

Thingvalla Line

Thingvalla Line was one of several large companies which were established at the initiative of Carl Frederik Tietgen. The aim of the company was to provide a direct route between Scandinavian ports and North America. Prior to its establishment, most Danish passengers had been conveyed by German shipping companies.

The new company established a ferry terminal at Larsens Plads on the Copenhagen harbourfront, a site that had been a combined shipyard and lumberyard until 1870. It was from here that its ships departed calling at Kristiania and Kristiansand before crossing the Atlantic to New York City. By including the Norwegian ports, the Thingvalla Line became an important competitor not only to the German companies but also to British-based companies. In favour of the new company, apart from the obvious advantage of providing a direct route, were their Scandinavian crews and a more homogeneous composition of passengers. Less favourable was their use of smaller and slower ships as compared to the larger German and British companies. This did not seem to affect the largely Scandinavian passengers as the line soon became quite popular. What was much worse for the company was that it had a series of accidents which became a setback for the line. Most notable were the sinking of the S/S Danmark in 1889 and the collision in 1888 of the S/S Geiser and S/S Thingvalla, both of which were owned and operated by the Thingvalla Line. In 1898, the company was acquired by DFDS which changed the name to Scandinavian America Line.

The Thingvalla Line’s Menu for Steerage

Subject to revision

Breakfast

- Barley- or wheat porridge, sugar, butter, wheat- and rye bread, salt herring or sausages and coffee

10 O’clock in the morning

- Gruel and milk for children and the sick

Lunch

- Sunday: Fresh meat broth with herbs and macaroni, fresh brisket of beef with brown gravy and potatoes

- Monday: Split peas, salted pork with mustard sauce and potatoes

- Tuesday: Sweet soup [soup made of fruit-juice and other things] with prunes, raisins etc., dried cod with mustard sauce and potatoes

- Wednesday: Cabbage soup (or rice pudding, beer, sugar, cinnamon etc.), salted pork with spicy sauce and potatoes (or stew with potatoes)

- Thursday: Fresh meat broth with herbs and rice with raisins, fresh beef with horseradish sauce and potatoes

- Friday: Split peas or beans, salted beef and pork with mustard sauce and potatoes

- Saturday: Sago soup [sago boiled in water flavoured with sugar, fruit-juice etc.] with prunes, raisins etc., dried cod with mustard sauce and potatoes.

3 O’clock in the afternoon

- Gruel and milk for children and the sick.

Evening

- Lobscouse or cheese and sausages, butter, wheat- and rye bread, tea, sugar etc.

- Condensed milk will be given for free to babies

- Fresh water is available in plentiful quantity

- Freshly baked bread is delivered everyday by the ship’s bakery

Wedding - Sponsors

The sponsors at a wedding acted as an official witness to ensure that the bride and groom were legally married and not too closely related to each other.

Typically, it was the father, a brother or a full-grown son to the bride and groom, respectively. On the bride’s side, it was originally the person that gave his daughter/sister/mother in marriage.

Women's rigths

Widows of masters of a craft, i.e. master baker, master carpenter, etc. were allowed, under certain conditions, to continue their late husbands’ trade. Most often she would be required to hire a qualified journeyman to assist with the day-to-day work though.

Women gained the right to vote in 1915.

Married women only gained the same rights as their husbands in 1925.

Working conditions

Working conditions were still harsh for the workers and smallholders in the last half of the 1800s, and well into the new century. The workdays were long and the work was grueling and exhausting. The wages of the servants, both in the cities and in the countryside were negotiable, there were no collective agreements or tariffs; supply and demand dictated the size of the pay.

In 1872, the Ministry of the Interior researched the conditions of the city- and farmworkers, and came to the conclusion that only in one single county – the county of Copenhagen – could a farmworker manage to make a – poor – living for a wife and two children, and only if he could work all year with no period(s) of unemployment along the way, which was quite unlikely. The wife and children of a family could work as well, and often did, to one degree or another, but this could in turn cause problems with the keeping of the household and children. Many wives of smallholders and farmworkers had jobs they could do at home, like spinning and sewing for small companies, but the pay was poor.